A bit over a decade ago, I was writing for a short-lived, Cincinnati-based music website called “I See Sound”. Sadly, the site is long gone (and the URL taken over by the usual web-squatters), but I still have some of the pieces I wrote.

The following piece was published in mid-November, 2005 (and slightly edited today).

“Well, have you heard Buckethead?”

I don’t remember his last name, the kid who asked me that question, but his first name was Brian (like Buckethead’s, coincidentally). We were freshmen in college that fall of 1992, and we were discussing guitar players.

At that point I was still very much a guitar nerd. For a couple years, when I started listening to music, I had been exclusively into rap. Upon picking up the guitar in 1990, however, I had sold all my rap tapes. I then got into metal, and along with it, a lot of guitar virtuoso stuff, like Joe Satriani, Steve Vai, and Yngwie Malmsteen. I delighted at the sheer speed with which some of these guys could play.

“No,” I told Brian, “I don’t know who that is.”

He proceeded to tell me he’d heard about a new record by a band called Praxis, with a weird guitar player who played amazing stuff. Of course, I’m sure he mentioned the KFC bucket on his head, but what I took away from that conversation was that I needed to hear this guy, not see him.

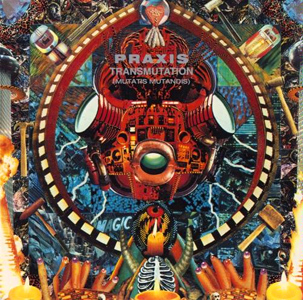

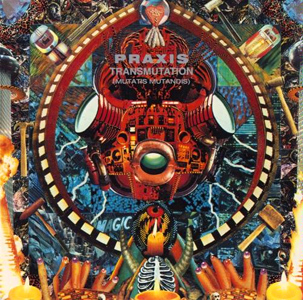

The album was Transmutation (Mutatis Mutandis), and within the next week I found the cassette at Headstone Friends, the college favorite record store in town, one I would become oh-so familiar with over the next four years. Back to my dorm room I went, straight to the tape deck, and put it in.

The album was Transmutation (Mutatis Mutandis), and within the next week I found the cassette at Headstone Friends, the college favorite record store in town, one I would become oh-so familiar with over the next four years. Back to my dorm room I went, straight to the tape deck, and put it in.

Luckily my roommate wasn’t around. He was a great guy, but his Right Said Fred ears would likely not be too pleased at the sound of “Blast / War Machine Dub“, the first track on side one. The “Blast” part of it I understood, consisting as it did of some heavy guitar and the fastest leads I think I’d ever heard. However, less than halfway into the four-minute track, things got weird, slowing down suddenly. At the time, of course, I had no idea what dub was, though I’d heard reggae and wasn’t overly fond. This didn’t remind me of reggae, though — this was weird.

Another thing that confused me was the presence, and sheer prominence, of the keyboards. Up until that point, I’d generally avoided them, preferring the guitar/bass/drums instrumentation of most metal, though the occasional piano intros and “texture” keyboard parts didn’t bother me. I had already scoured the liner notes for any familiar names and found none, so re-reading “Bernie Worrell: synthesizer, clavinet & vital organ” didn’t demystify it at all.

Nor did the next track on the record, “Interface / Stimulation Loop“, which began with an incredibly simple-but-heavy three note riff. The organ and guitars played in unison over a very funky beat that I wouldn’t have expected in metal. Of course, by this point I had already realized that this was no metal album, and of course Brain was no metal drummer. This guy was varied, in both style and technique.

Each track on the album seemed weirder and more diverse than the last, incorporating not only metal, dub, and funk, but also jazz, hip-hop, and experimental music. The one vocal track, “Animal Behavior“, featured Bootsy Collins simply being Bootsy, though the section of lyrics that name-checked the rest of the band (“Hey Buckethead, what’s in the bucket, man?”) definitely seemed a bit left-of-center.

The last track on the record, the huge “After Shock (Chaos Never Died)” was the biggest conundrum, though. By this time, getting my head around funk was no problem. Also, Buckethead was definitely the feature here, so I had plenty to chew on, with his two-minute guitar solo daring me to figure out its twists and turns. It had many, too, from the mile-a-minute stuff that I’d previously (and foolishly) thought was a good litmus test of quality, to slow, oddly-paced little melodies during a breakdown section. The pop-culture-obsessed Buckethead even slipped in a bit of the melody from “It’s a Small World”, a weird, three-second chunk of familiarity in a piece that was very foreign to me (and about to become even more so). After a little drum breakdown, the track devolved into a free-form collage jam session, focusing initially on Worrell’s organ, but eventually incorporating noise elements, most likely explained by Buckethead’s secondary credit of “toys”. As unprepared as I was for the genre-jumping to which I was subjected so far in the record, in no way was I ready for nearly twelve minutes of experimental music.

That didn’t stop me, of course, from immediately turning the tape over and listening to the entire album again, and then repeatedly over the ensuing weeks and years. Truth be told, back then I usually fast-forwarded through the experimental section at the end, but the rest of the record was fascinating. I’d heard music I liked before, but not with the staying power this had.

Transmutation broke “genre” in my head. Specifically, until then, I had been under the impression that one could really only like one genre of music — that’s why I had sold my rap tapes when I started listening to metal. Some of it could be chalked up to capricious youth, but mostly I just didn’t think I had room in my head for more than one kind of music. Buckethead’s weird metal shredding on the record gave me something familiar to latch onto, but once I became familiar with it, I realized that I liked it all.

After that, it wasn’t too long before I was getting some of those rap tapes again, and other things, too. I delved into the discographies of the people involved, discovering that AF Next Man Flip was none other than Afrika Baby Bam, the dj for the Jungle Brothers, whose music had been in the purge only a couple years earlier. I discovered that Bootsy and Bernie Worrell were decades into their careers at that point, and I made repeated trips to the campus radio station to make tapes of the vinyl of their releases there.

The one person most important on the whole record, though I didn’t realize it, had no specific instrument credit, so I didn’t notice him at first. Over the next few years I gradually came to understand the significance of the line “Conceived and Constructed by Bill Laswell”. I saw his name on the later Praxis records, too, and when I got Buckethead’s pseudonymous Death Cube K records, there was Laswell again. When I got that Public Image Limited plain-wrap Album because Steve Vai had played on it, guess who had produced and played on it as well? Correct. Later, when I became a dj myself and picked up Herbie Hancock’s seminal “Rockit” 12″ single, arguably one of the most influential records in hip-hop, it came as little surprise to find it had been co-written by Laswell. Now I have over a hundred or more (no exaggeration) albums with his name credited in some active role.

To this day I still find new things in Transmutation, whether it be noticing a quiet guitar line buried deep in the left channel, or understanding how Bootsy and Bernie interact in a way that doesn’t happen without years of playing together. Even sitting here writing this, I realize that my taste in snare drum sound comes from Brain’s drumkit on this record.

Transmutation permanently changed how I listen to music, and is directly responsible for my exposure to, and familiarity with, a good portion of my all-time top ten artists. So, thanks, Brian Whatever-your-last-name-was; you inadvertently helped make me who I am today.

The album was

The album was